Summary

Contents showVulvovaginitis is a frequent condition encountered in gynecological consultations. Vulvovaginitis is defined as the inflammation of the vulva and vagina, most often produced by infectious agents in women of reproductive age.

Vulvovaginitis is classified into two main categories according to its etiology: infectious and non-infectious vulvovaginitis. Infectious causes of vulvovaginitis are the most common and include bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and sexually transmitted infections, such as Trichomonas vaginalis, Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, and Chlamydia trachomatis infections.

Diagnostic workup of vulvovaginitis includes a detailed anamnesis, gynecological examination, and microscopy. Treatment strategies are indicated in accordance to the results of diagnostic studies investigating the underlying cause.

Diagnosis and Management of Vulvovaginitis – Introduction

Vulvovaginitis is a fairly common condition in gynecological consults. It is defined as the inflammation of the vulva and vagina, usually secondary to infectious agents in reproductive-aged women. The most frequent symptoms include discomfort, pruritus, and vaginal discharge. Patients should be initially evaluated by detailed anamnesis, gynecological examination, and, if available, microscopy. Some patients require more detailed evaluation and further studies to arrive at a correct diagnosis. Empiric treatment should be avoided due to the risk of an incorrect diagnosis. (1)

This article emphasizes the most important aspects of each possible etiology and the different treatment options to consider.

Definition of Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is defined as the inflammation of the vulva and vagina that can be caused by infectious or non-infectious etiology. It’s characterized by vaginal discharge, inflammation, pruritus, odor, burning sensation, dyspareunia, spotting, and possible abrasions, among others, and usually impact the quality of life. (2)

Epidemiology of Vulvovaginitis

It is estimated that the majority of females will experience a vaginal infection during their lifetime. Vaginitis is responsible for more than 10 million consults in the US yearly. More than 90% of infectious vaginitis are caused by bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis. (3) Treatment for bacterial vaginosis, which is the most common form, represents $1.3 billion per year. (4) Vaginitis caused by Trichomonas Vaginalis is the most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infection (STI), affecting 3.7 million people annually in the US. (2)

Infectious vaginitis is not out of the regular course in postmenopausal women but, in this group of patients, other etiologies must be considered. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause is due to vulvovaginal atrophy and affects 27 to 84% of postmenopausal women. Symptoms include vaginal dryness, burning, irritation, and urinary symptoms, such as dysuria and recurrent infections. (5)

General Management of Vulvovaginitis

Anamnesis and Physical Examination

To begin with, it is necessary to have a clear idea of the patient’s medical history: clinical conditions, medical treatments, contraceptive methods, menses, vaginal hygiene practices (e.g., douching), sexual behaviors, allergies, and if there was self-treatment with over-the-counter medication. It is essential to draw out information about the symptoms’ location, description, and duration.

After a complete anamnesis, it is essential to examine the patient correctly. The gynecologic examination should start with inspecting the vulva, pelvis, and perinium, and continue with palpation seeking inguinal adenopathies. Later, speculoscopy should be careful to evaluate cervical anatomy and detect any bleeding or lesions; vaginal discharge must be assessed, looking at the following characteristics: color, smell, aspect, consistency, and quantity. Finally, and if it is possible, a sample of vaginal discharge must be collected with a cotton swab and tested for pH and microscopy. (6)

The Need for Diagnostic Workup

Clinicians should not rely on symptoms entirely to distinguish confidently between the causes of vaginitis because it can result in inaccurate or incomplete diagnoses and elevated recurrence rates. (4) FDA-approved molecular tests have shown higher specificity and sensitivity and have been recommended if available. (3)

Classification of Vulvovaginitis

| Infectious | Non-infectious |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) Candida Vulvovaginitis (CVV) STIs: Trichomonas Vaginalis (TV), Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia Trachomatis | Allergic and Irritative Vaginosis Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis Genitourinary Syndrome Cytolytic Vaginosis |

Infectious Vaginitis

Bacterial Vaginosis

Overview

It is the principal cause of vulvovaginitis worldwide and the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge in patients of reproductive age. Prevalence is higher in African-American and Hispanic women. (6-8)

The reason for this condition is a change in the vaginal microbiota generated by the loss of hydrogen peroxide produced by Lactobacillus species toward more diverse bacterial species, including Gardnerella Vaginalis, a gram variable rod, Prevotella species, Mobiluncus species, and others. (9,10)

Risk and Protective Factors

Some of the most frequently associated risk factors include:

- Ethnicity,

- reproductive age,

- lack of condom use (11),

- HSV-2 seropositivity (12),

- vaginal douching (13, 14),

- and pregnancy (15, 16).

BV prevalence has been reported to be higher among women with copper-containing IUDs. (17,18) On the other hand, hormonal contraception (19,20) and male circumcision might protect against BV development. (21) It is essential to know that although BV is linked to hetero and homosexual activity (22) and rarely occurs in patients who have never been sexually active, it is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, so treatment for the partner is not recommended. (23-29)

Presentation and Diagnosis

Many patients with BV are asymptomatic; those who present symptoms usually report abnormal watery, white-gray vaginal discharge, often with a fishy odor. Symptoms usually appear during menses. (30,31)

The diagnosis is based on Amsel clinical criteria or Gram stain with Nugent scoring. (32,33) In research settings, Gram stain with Nugent scoring is considered standard criteria for BV diagnosis; however, it is not practical; therefore, Amsel criteria typically are used for the diagnosis. (33)

| Amsel Criteria: 3 of the 4 criteria are required (33) |

|---|

| Thin, homogeneous gray-white or yellow discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls |

| Clue cells identified on wet mount preparation |

| Vaginal pH > 4.5 |

| Positive Whiff test (fishy odor) |

The presence of bacterial vaginitis is associated with an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections; consequently, the patient must be tested for HIV and other STIs. Pregnant women have a higher risk of preterm delivery, premature rupture of membranes, spontaneous abortion, intra-amniotic infection, and postpartum endometritis. (34-36) At any rate, there is no recommendation for routine screening for BV among asymptomatic pregnant women. (37)

Treatment of Bacteria Vaginosis

Recommended regimen based on CDC 2021 guidelines: (38)

| Recommended regimen | Alternative regimen |

|---|---|

| Metronidazole 500 mg orally 2 times/day for 7 days. Metronidazole gel 0.75% one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally, once a day for 5 days Clindamycin cream 2% one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days | Clindamycin 300 mg orally 2 times/day for 7 days Clindamycin ovules 100 mg intravaginally once at bedtime for 3 days * Secnidazole 2 g oral granules in a single dose** Tinidazole 2 g orally once daily for 2 days Tinidazole 1 g orally once daily for 5 days |

* Clindamycin ovules use an oleaginous base that might weaken latex or rubber products (e.g., condoms and diaphragms). Use of such products within 5 days after treatment with clindamycin ovules is not recommended.

** Oral granules should be sprinkled onto unsweetened applesauce, yogurt, or pudding before ingestion. A glass of water can be taken after administration to aid in swallowing.

Refraining from alcohol use while taking metronidazole (or tinidazole) is unnecessary. (39) The warning against the simultaneous use of alcohol and metronidazole was based on laboratory experiments and individual case histories in which the reported reactions were equally likely to have been caused by alcohol alone or by adverse effects of metronidazole.

In addition, it is a good medical practice to advise women to refrain from sexual activity or to use condoms consistently and correctly during the BV treatment regimen. (38)

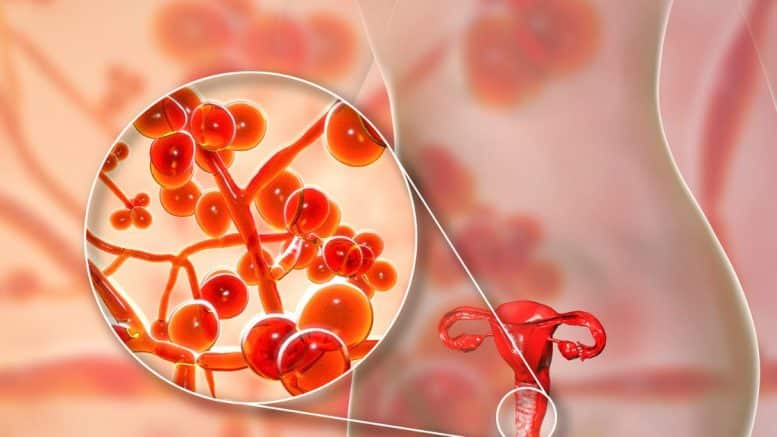

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC)

Overview

It is the second most common cause representing 17–39% of vulvovaginitis; statistics show that 29 – 49% of female patients report at least one-lifetime episode. (40)

Risk Factors

Among the risk factors are:

- Medications (antibiotics, steroids, immunosuppressive therapies),

- pregnancy,

- excessive moisture,

- smoking cigarettes,

- diabetes mellitus,

- and some congenital pathologies (AIRE gene mutation) (6).

Presentation

The most common clinical features are erythematous vulva and vagina, dyspareunia, external dysuria, and intense pruritus with vaginal burning sensation, fissures, and abrasions. Characteristic vaginal discharge is white, thick, odorless, and has a “cottage cheese” appearance. (38)

Classification

Candidiasis infection can be classified as uncomplicated or complicated.

| Uncomplicated VVC | Complicated VVC |

|---|---|

| All of the followings: Sporadic or infrequent VVC Mild-to-moderate VVC Likely to be Candida Albicans Non Immunocompromised women. | Any of the following Recurrent VVC Severe VVC Non-albicans candidiasis Diabetes, immunocompromising conditions, underlying immunodeficiency, or immunosuppressive therapy |

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of VVC is based on clinical signs and symptoms and a wet preparation (saline, 10% KOH) of vaginal discharge demonstrating budding yeast, hyphae or pseudohyphae, or positive mycological culture. VVC is associated with normal vaginal pH (< 4.5). If candida cultures cannot be done, or the results of the wet mount are negative with existing signs and symptoms, empiric treatment should be prescribed. (38)

Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Recommended treatment for uncomplicated VVC is based on short-course topical formulations (i.e., single dose and regimens of 1–3 days). Medications recommended by CDC are: (38)

| Over-the-Counter Agents | Prescription Agents |

|---|---|

| Clotrimazole 1% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 7-14 days Clotrimazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 3 days Miconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 7 days Miconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 7 days Miconazole 4% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 3 days Miconazole 100 mg vaginal suppository one suppository daily for 7 days Miconazole 200 mg vaginal suppository one suppository daily for 3 days Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository one suppository for 1 day Tioconazole 6,5% ointment 5 g intravaginally in a single application | Butoconazole 2 % cream 5 g intravaginally in a single application Terconazole 0.4% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 7 days Terconazole 0.8% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 3 days Terconazole 80 mg vaginal suppository daily for 3 days Oral agent: fluconazole 150 mg orally in a single dose. |

Complicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Recurrent is defined as three or more episodes of symptomatic VVC in less than a year. (41) Most of these are caused by Candida Albicans and respond well to a short-term duration of oral or topical azole therapy.

- In any case, a longer duration of initial therapy and a maintenance antifungal regimen is recommended. Some of the most useful initial regimens are 7–14 days of topical therapy or a 100 mg, 150 mg, or 200 mg oral fluconazole every third day for 3 doses (days 1, 4, and 7).

- For a maintenance regimen, oral fluconazole (100mg, 150 mg, or 200 mg) weekly for 6 months is prescribed. If this regimen is not feasible, topical treatments used intermittently can also be considered.

- Severe VVC is based on the severity of the symptoms, such as extensive vulvar erythema, edema, excoriations, or fissure. In this case, 7–14 days of topical azole or 150 mg of fluconazole are recommended in two sequential oral doses (the second dose 72 hours after the initial dose). (38)

- The optimal treatment of non-albicans VVC remains unknown; however, a longer duration of therapy for 7 or 14 days with a non-fluconazole azole regimen (oral or topical) is recommended. If recurrence occurs, 600 mg of boric acid in a gelatin capsule administered vaginally once daily for 3 weeks is prescribed. This regimen has clinical and mycologic eradication rates of approximately 70%. If symptoms recur, a referral to a specialist is advised. (42)

Trichomona Vaginalis (TV)

Overview

Even though it is one of the most prevalent STIs in the United States, more than 50% of patients have minimal or no genital symptoms; for that reason, it can last as an untreated infection for the long term. The danger of untreated Trichomonas is preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, and a higher risk of HIV acquisition. When a diagnosis is performed, it is vital to evaluate other STIs and test and treat sexual partners. (6, 43)

Presentation

Symptomatic patients report:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge,

- itching,

- burning,

- or postcoital bleeding.

The discharge usually is abundant, purulent, and odorous. It is associated with an elevated pH level. Vulvar inspection shows erythema, edema, and significant inflammation.

Diagnosis of Thricomona Vaginalis

To confirm the diagnosis, microscopy reveals flagellated and undulating Trichomonas and increased white blood cells with a sensitivity of 50 to 60%. A higher sensitive and specific test, such as nucleic acid amplification, is preferred. Alternative diagnostic options include FDA-approved commercial tests or vaginal culture, which should take five days. In practice, the most used method might be the microscopic evaluation of wet preparations of genital secretions due to its low cost. However, the absence of trichomonas in samples does not rule out a TV infection. (4,6,41)

Treatment of Trichomoniasis

CDC recommended treatment is metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days or tinidazole 2 g orally in a single dose. A single dose of 2 g by mouth is recommended in male partners. In refractory disease, tinidazole 2 g by mouth daily for 7 days. (41)

Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis

Overview

It is a chronic inflammation of the vulva and vagina without identifying a specific pathogen. The vaginal microbiome has nearly absent Lactobacilli with facultative anaerobes (such as Enterococcus Faecalis, Streptococcus Agalactiae, and Escherichia Coli). (44, 45)

Presentation

Clinically patients refer vaginal discharge and irritative vulvovaginal symptoms. (44)

It is more frequent in perimenopausal women and has been associated with an increased risk of urinary tract infections, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, and miscarriage. (44)

Diagnosis of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis

Required diagnostic criteria: (44, 45)

| Symptoms: abundant purulent and odorless vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, pruritus, burning or irritation |

| Clinical Signs: vaginal inflammation characterized by ecchymosis, petechiae, erythema, or erosions. |

| Vaginal pH > 4.5 |

| Microscopy: increase of parabasal and inflammatory cells, leukocyte-to-epithelial cell ratio greater than 1:1, and exclusion of other germs (VB, TV, Chlamydia, Gonococcus) |

Treatment of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis

Treatment is not entirely defined due to the lack of randomized trials. The recommendation is to use antibiotics, such as topic clindamycin (2% vaginal cream daily for 3 weeks and then biweekly), to treat anaerobic bacteria and anti-inflammatory agents like vaginal hydrocortisone (300-500 mg/day for 3 weeks and then biweekly for 6 months). Vaginal estrogen might help reduce the duration of inflammatory symptoms. (44,46)

Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause

Overview

It is defined as symptoms and signs resulting from estrogen deficit in the female genitourinary tract. It is highly prevalent in postmenopausal women. Genital symptoms include dryness, burning, and irritation, as well as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Urinary symptoms involve dysuria, urgency, and recurrent urinary tract infections. All of these, generally, are progressive without effective therapy.

Diagnosis

During the examination, vulvar atrophy, vaginal dryness, introital stenosis, and clitoral atrophy are visible. After a while, the vulvar and vaginal epithelium can result in friable and hypopigmentation. (5, 47)

Treatment

First-line therapies include non-hormone vulvar and vaginal lubricants for sexual activity and long-acting vaginal moisturizers used regularly. There is no evidence that products with hyaluronic acid have a more significant benefit than non-hyaluronic acid lubricants or moisturizers.

Even though there are no sufficient clinical trials, the North American Menopause Society recommends regular, gentle vaginal stretching exercises. (5)

Hormonal therapy with low-dose vaginal estrogens is widely recommended. Subjective results may take 4 to 12 months, and continued therapy is generally required because symptoms are likely to recur on cessation of treatment. There are multiple forms of vaginal estrogen treatment, but Cochrane concluded they had similar efficacy after reviewing 19 trials. (23) Usually, vaginal therapy provides sufficient estrogen to the genitourinary system. A Cochrane review determined that vaginal estrogens improve incontinence and urinary symptoms. (48)

Oral hormonal therapy is exclusively recommended with concomitant vasomotor symptoms. (5)

Cytolytic Vaginosis

Overview

Its name is given due to the lysis of vaginal epithelial cells caused by the abundant growth of Lactobacilli. It is also known as Lactobacilli overgrowth syndrome or Doderlein’s cytolysis. (49)

The etiology is poorly understood. Patients complain of intense pruritus and copious white vaginal discharge, which may simulate a VVC. The diagnosis is confirmed by abundant Lactobacilli covering the fragmented epithelial cells that may be confused with the “clue cells” of BV, these are therefore called “false clue cells.” It is confirmed by the absence of Trichomonas Vaginalis, Gardnerella, or Candida on wet smears.

Treatment consists in reducing Lactobacilli by douching with a sodium bicarbonate solution. Douches are carried out twice weekly with 30 to 60 grams of baking soda every two weeks.

Disclosures

The author does not report any conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes and is not intended to treat disease or supplant professional medical judgment. Physicians should follow local policy regarding the diagnosis and management of medical conditions.

See Also

Diagnosis and Management of Anaphylaxis in Adults

Acute Uncomplicated Pyelonephritis in Adults

Follow us