Summary

Contents showDistal radius Fractures are the most common injury in adults. They involve traumatic lesions of the distal ulna and radius and the proximal carpal bones, as well as associated soft tissue structures.

Distal radius fractures are classified into extraarticular, partial articular, and complete articular fractures. Classic eponyms that refer to distal radial fractures include Colle’s fracture, Smith’s fracture, Barthon’s fracture, Chauffer’s fracture, and Die-punch Fracture.

Patients presenting with distal radial complain of wrist pain, swelling, and deformation, along with a history of a traumatic event.

Diagnosis is based on imaging, including X-ray, CT scan, and MRI (in cases of suspicion of soft tissue injuries).

Treatment strategies for distal radius fractures include non-operative and operative management. Among the latter, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and external fixation are included.

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults – Introduction

Distal radial fractures are common injuries that patients can present with at any age. Distal radial fractures have a broad spectrum of variety, and appropriate management includes medical and surgical treatment with novel surgical techniques expanding the field of Orthopedic Surgery, such as arthroscopy-assisted fixation.

This article provides relevant information to physicians for reviewing indications of surgical treatment, differentiation of emergent vs. non-emergent injuries, and management and treatment implications.

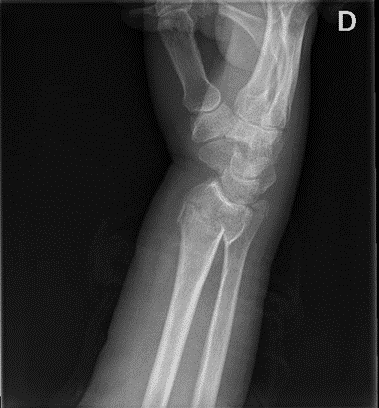

Case example: A 65-year-old woman falls from her own height with her wrist hyperextended (Figure 1). In the trauma bay, radiographs confirm a displaced distal radius fracture. After proper temporary immobilization with a splint and a sling, open reduction, and internal fixation surgery is scheduled in the next few days.

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Figure 1. A lateral radiograph of the distal radius showing an extra-articular fracture with dorsal displacement and ulnar styloid fracture.

Anatomy

The radius is one of the two forearm bones. The proximal part of the bone articulates with the humerus and the ulna to compose the elbow joint. These two forearm bones are connected to each other through the interosseous membrane. The radius then widens at its distal part and articulates with the proximal row of the carpus (the scaphoid and the lunate bones) to form the wrist joint (or radiocarpal joint) with movement in the sagittal plane (flexion and extension) and coronal plane (adduction and abduction). And it also articulates with the distal ulna (the distal radioulnar joint), which is involved in the pronation-supination movement (axial plane).

Many soft structures, such as ligaments or tendons, originate or cross the wrist, and neurovascular structures, such as the radial and ulnar arteries and the median, ulnar, and radial nerves, travel through the wrist to the hand.

Epidemiology of Distal Radial Fractures

Distal radius fractures are adults’ most common injury, accounting for approximately 17.5% of fractures [1]. The incidence of these fractures follows a bimodal distribution: first peak in the pediatric and second peak in the elderly population. While in the pediatric population, the incidence is greater in males, fractures in the elderly population occur more frequently in females (2-3:1) [2].

While in the younger population, these injuries derivates from high-energy trauma, in the elderly, a fall on an outstretched hand is the most common mechanism of production. Newer studies show the worldwide incidence of distal radius fractures is increasing yearly owing to the overall potential to live longer with comorbidities such as osteoporosis [3].

Etiology

Most distal radius fractures in the elderly population are produced by falling on an outstretched hand. In the younger, high-energy trauma is needed to fracture the bone.

Associated conditions include ulnar styloid fracture, distal radioulnar joint injuries, and ligamentous injuries: Triangular FibroCartilage Complex (TFCC) injuries, lunotriquetral ligament, and scapholunate ligament injuries.

Classification of Distal Radial Fractures

There are many classification systems for these types of fractures.

One of the most used, the AO Classification (Table 1), divides fractures into extra-articular, partial intra-articular, and complete intra-articular [4]. This classification includes a total of 27 subtypes of distal radius fractures, so the reliability and reproducibility can be lower [5].

Table 1. AO classification for distal radius fractures.

| 2R3-A (extraarticular) | 2R3-B (partial articular) | 2R3-C (complete articular) |

|---|---|---|

| A1: radial styloid avulsion | B1: sagittal (Chauffer) | C1: simple articular and metaphyseal |

| A2: simple | B2: dorsal rim (Barton) | C2: comminuted metaphyseal |

| A3: wedge or multifragmentary | B3: volar rim (reverse Barton) | C3: multifragmentary articular |

Eponyms

There are many distal radius fracture eponyms, including [7]:

- Colles’s Fracture: an extra-articular fracture with dorsal displacement.

- Smith’s Fracture: an extra-articular fracture with volar displacement.

- Barton’s Fracture: a partial articular fracture with a volar fragment, displaced volarly. Reverse Barton’s fracture is a dorsal fragment displaced dorsally.

- Chauffer’s Fracture: a partial articular fracture with a radial styloid fracture, high energy.

- Die-punch Fracture: an articular fracture, depressed fracture of the lunate fossa of the distal radius.

Clinical presentation

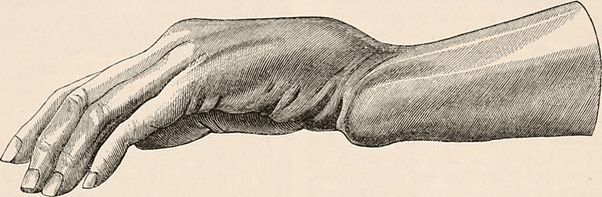

Usually consists of wrist pain, swelling, and deformation. The motion of the wrist and fingers can be limited by pain. For Colles’ fracture, the classic deformity is called “dinner fork deformity” (Figure 2) because of its reminiscence to the back of a fork.

In high-energy trauma, it is necessary to investigate for open fractures and must inspect the neurovascular status (radial and ulnar artery pulse, capillary filling, and status of the radial, median, and ulnar nerves).

Assessment of associated injuries should include palpation of the elbow (Essex Lopresti injury), palpation and stress testing of the distal radioulnar joint, the anatomical snuffbox (occult scaphoid fracture), and the ulnar carpal region (distal ulnar fractures and TFCC injuries).

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Figure 2. Dorsal displacement is seen in dorsally angulated distal radius fracture, creating a fork-like appearance. Image from page 732 of “The cyclopædia of anatomy and physiology” (1849) Todd, Robert Bentley, 1809-1860 (Public domain).

Imaging

Radiographs are the first step to diagnosis and often the only one needed. Mandatory views include true AP and lateral views. The oblique view can help recognize hidden patterns. A break in the cortices of the bone should be seen, and associated bone injuries can also be diagnosed.

Radiographic parameters of the distal radius are measured in these two views. These include radial inclination (AP view), radial height (AP view), articular step-off (AP view), and volar tilt (lateral view) [8].

Table 3. Radiographic parameters of distal radius

| Measurement | Normal | Acceptable criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Radial inclination | 22º | <5º of change |

| Radial height | 10 mm | <5 mm of shortening |

| Volar tilt | 11º | <5º of dorsal angulation |

| Articular step-off | 0 mm | <2 mm |

For intraarticular fractures, a CT scan should be taken. It allows visualization and individualization of fragments, measurement of articular step-off, and surgical planning. MRI is taken when a soft-tissue injury is suspected, including TFCC and intercarpal or radiocarpal ligament injuries.

Medical management of Distal Radial Fractures

Non-operative management:

The initial treatment for any fracture is immobilization. In most cases, it can be achieved through closed manual reduction and the use of a splint or cast. For those fractures with joint steps of less than 2 mm, a dorsal tilt of fewer than 10 degrees or within 20° of contralateral radius, or radial shortening of less than 3 mm, non-surgical treatment can be performed [9].

The reduction maneuver consists of traction on the axis of the radius and counter traction at the level of the elbow, dorsal hyperextension to create space, and then flexion. The fracture can be immobilized using a sugar-clamp splint, or more commonly, a circular cast, with the wrist in slight palmar and ulnar flexion. The debate today is whether the elbow should be immobilized as well. The latest studies indicate no substantial differences between below-elbow and above-elbow casts in terms of fracture reduction maintenance or clinical outcomes [10].

After performing the closed reduction, new x-rays will be taken (Figure 3 and Figure 4). In the case of an inherently stable fracture with acceptable reduction, definitive treatment will consist of a cast for approximately 4-6 weeks, with weekly serial radiographic follow-up to determine that there are no secondary displacements within the cast. After this period of casting, movement of the wrist must start. A supervised physical therapy program is more effective for improving function in the short- and medium-term compared to a home exercises program in patients older than 60 years with extra-articular distal radius fractus without immediate complications [11].

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Figure 3. Pre-reduction Lateral and AP radiographs of a distal radius fracture.

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Figure 4. Post-reduction lateral and AP radiographs of distal radius fracture with a below-elbow cast.

One way to know if the fracture is inherently unstable is by using the LaFontaine criteria [12] in pre-reduction radiographs, which are:

- severe osteoporosis

- associated ulnar fracture

- dorsal comminution > 50%, palmar comminution, intraarticular comminution

- dorsal angulation > 20°

- initial displacement > 1cm

- initial radial shortening > 5mm

Lafontaine criteria are a predictor of instability. Radial shortening is the most important risk factor, followed by dorsal comminution. If three or more risk factors are encountered, the chance of reduction loss is higher; therefore, operative treatment should be considered.

Operative Management

Surgical treatment of radius fractures consists of three options: closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, open reduction and internal fixation, or external fixator.

Closed reduction and Percutaneous pinning

Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning modality is losing popularity as a treatment modality for distal radius fractures. However, in select cases, this technique may have advantages relative to open reduction and internal reduction [13]. Indications are quite precise: highly displaced and unstable fractures in very young patients or extra-articular fractures with stable volar cortical bone in adults.

Kapandji’s intrafocal technique is the most used. It consists of placing two or three pins inside the fracture gap. One pin goes from dorsal to volar and is utilized for achieving the volar angulation, and another from radial to ulnar and is used for acquiring radial inclination and radial height. These pins are employed as a lever for fracture reduction, and once a good reduction is achieved, the pins are driven until they engage the opposite cortex [14]. Other techniques are extrafocal, starting from one fragment to another across the fracture; generally, one pin through the radial styloid and the other parallel to the articular surface of the radius, engaging the distal ulnar cortex [15].

Complications of this technique include pin tract infection and nerve damage (especially radial sensory nerve in the radial styloid site).

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF)

The most widely used treatment nowadays is open reduction and internal fixation with a plate. New techniques and new plate designs have made it possible to obtain very good results, supporting the subchondral bone without collapse, a solid structure that maintains fracture reduction and also allows early mobilization.

Indications include radiographic findings indicating instability (the LaFontaine criteria), displaced intra-articular fractures greater than 2mm, articular margin fractures (Barton’s fracture), extra-articular with volar displacement (Smith’s fracture), the Die Punch fracture, or progressive loss of volar tilt and radial length following casting.

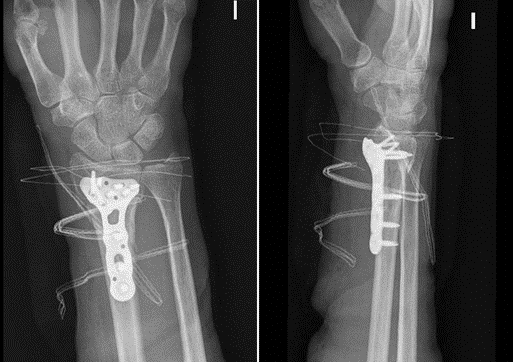

Commonly, a volar approach (the modified Henry’s approach) is used, and a volar plate with locking screws is preferred (Figure 5). Some fracture patterns, such as reverse Barton (a partial articular dorsal fragment) or multi-fragmentary articular fractures, may require a dorsal approach and the placement of specific fragment plates.

Another advantage of open reduction and internal fixation is the possibility of placement of autologous bone graft or phosphocalcic cement, which are indicated in fractures with bone loss, great comminution, or in cases of malunion [16]. And in recent years, arthroscopy-assisted reduction of articular fractures has become very popular, which among its advantages, allows direct visualization of the joint, minimizing the risk of residual articular step-off and the simultaneous treatment of concomitant injuries such as intercarpal ligamentous injuries or TFCC injuries [17].

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Figure 5. ORIF of distal radius fracture with a volar locking plate.

Complications of ORIF include tendon rupture (FLP or EPL) and malposition of screws (intraarticular screws).

External Fixation

Indications for external fixation include open fractures and highly comminuted fractures, which require a joint-spanning procedure [18]. In other medical centers, external fixation is usually done combined with percutaneous pins for restoration of palmar tilt and radial length in comminuted articular fractures [19]. Complications of this method include stiffness, pin tract infection, malunion, and nonunion.

See Also

Diagnosis and Management of Vulvovaginitis

Diagnosis and Management of Anaphylaxis in Adults

Acute Uncomplicated Pyelonephritis in Adults

Initial Management of Hip Fractures in Adults

Community Acquired Pneumonia in Adults

References:

[1] Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury 2006;37:691–7.

[8] Medoff RJ. Essential radiographic evaluation for distal radius fractures. Hand Clin 2005;21:279–88.

Follow us